Her parents called her Rome. A name out of a book. But some other kids looked in books too and were constantly teasing her saying FALL OF ROME, FALL OF ROME. So she changed her name, to Stalingrad, and other kids kept their distance.

At 12 she changed her name again, to Joanne. People whispered that she talked to a history teacher who knew lots about Old Times and after that she changed it. Who knows? In any story there is a lot you cannot be sure about and for that reason people are always criticising the ones that tell stories.

It was certainly a teacher that first recognised her talents because her parents were dead by then. The teacher called her privately to a part of the classroom and said, ‘You have got talent. Do not waste it. Do not tell anyone’, which seemed like contradictions. Later, during a long air raid, the same teacher whispered that the talent could bring both riches and trouble. Joanne was scared. The teacher said ‘Do not be scared, the bombs never fall on this side of the city or compound’. Joanne said she was not scared of the bombs, she was scared of the talents. The teacher said it was okay to be frightened of talents. ‘Do not take the talents for granted’, the teacher said, ‘Do not think about the talents’, which also seemed like contradiction.

Joanne got a job in a hotel on the seafront, inside the Inclusion Zone. Mostly it was scooping bones from dirty water, wiping plates after banquets. When the kitchens were quiet she took to the stage, dancing in a chorus of Orchid Girls, or standing pretty by some guy that had Post Traumatic Stress Disorder but pretended to be a magician. It was strange the Acts those soldiers liked to watch. They liked the Card Tricks and the Neon Lives, they liked the Knife Throw and the Body Bag. But more than anything they loved the Futures.

The guy who did Futures in those days was called Omar. He made a big play of everything, as was the style of the time, speaking in a loud voice, fluttering his eye lids, shaking, twitching, moaning and acting all mysterious. Some of it was pure theatre, some of it was symptoms and the rest was just side effects of the stress medications. He was worst in winter time, because it brought up memories of trenches and snow. They weren’t his memories but that didn’t matter to him and he’d writhe at night and call out voices saying please please and no no and all that old soldier talk that no one wants to hear anymore.

He died when Joanne was 15. Then came another bloke to do Futures but he was caught stealing food from the Palace gardens and got executed. Then for some time there was no Futures in the hotel and the soldiers grew restless and the Manager came and asked her (Joanne) if she would do it and she remembered the old advice that her talent could bring success and she forgot the part that it could bring trouble which is often the way in stories, that the idiots inside them have such poor or selective memory and this fact leads to their end.

Her first few appearances were soon the stuff of legend. Soldiers came from miles around to see her do Futures. Soft and intermittent was her voice as a line on a satellite phone, or so the poets say. Generals came and demanded private audience. The heads of a Microchip Corporation also bade her do Futures for them. Her Futures were warm like honey, soft like skin of a boy, sharp like Exactor Knives.

When the soldiers withdrew she was hunted as a collaborator and many of her compatriots from the Hotel days were killed or forced to live in the mountains as vagabonds or anonymous creatures. Joanne survived though and soon found the patronage of a certain powerful man who had her do Futures for him and members of his Entourage. The Futures she did were still pleasing; warm like the sun, soft like the breathing of a feverish child, sharp like the tongue of a whore.

One day they brought a man and bade her do Futures on him. It was a weird gig—the guy was bound and smelled of fear and possibly faeces, they kept a bag on his head and a gun to his back.

‘I cannot do Futures on a man I cannot see’, she said. ‘That is not the way’.

So the warriors removed the bindings, and the bag from this man’s head.

The man was very beautiful.

‘I cannot do Futures on a man that has a gun to his back’, she said.

So the warriors took the gun away and returned it to the metal cabinet where weapons were stored.

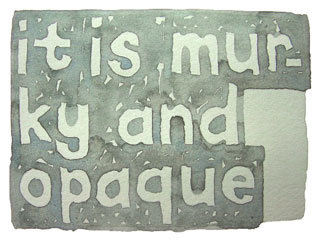

Then Joanne was nervous. She stepped forwards and laid her fingers at the skin of the captive’s neck whereupon the man stirred and made an animal sound. He looked in her eyes but she looked away. She could feel his Futures then, strong like the pulse in his neck but when she spoke she lied, and said no, that she could not find it, that the captive had no Futures she could see, only something murky and opaque.

Her patron laughed at this and commanded that she give up nonsense and tell the truth.

Joanne refused.

Six nights they gave her in a prison cell at the Radisson to change her mind and in those nights she thought about her old teacher’s words that her talents might bring both riches and trouble.

On the next day she was taken once again to tell the Futures of the captive but the outcome of that meeting is itself murky and opaque, lost in the passage of time, unknown to the poets and in any case not recorded in any version of her tale.